So I tried my hand at making soap yesterday. The old-fashioned way with lard. And homemade lye from ashes. On a fire. In a cast iron pot. Yes, I know I can buy soap at the store, but this is for my work at Locust Grove. I'm trying to learn to make soap the way it would have been done in 1816. Plus, if we ever have to live off the grid, at least we will be clean!

Anyway, I trained one day last week at Squire Boone Caverns. The lady I worked with was very nice, and I learned a lot of things I didn't know like about the caustic nature of lye and how to counteract it if you get some on you accidentally (wipe with vinegar) and how to tell if the soap mixture has come to "trace" and is ready to pour. Unfortunately, because their soap is made to sell commercially, she has to use commercial lye, which comes in flakes and is measured to the 100th of an ounce on a digital scale. It's sodium hydroxide and not potassium hydroxide, which you get from ashes, so that wasn't going to help me. She also measures the temperature of the solutions with a thermometer to make sure they are within 10 degrees of each other. Obviously, I can't use commercial flakes, a digital scale or a thermometer when I'm in 1816, so I had to turn to YouTube. I watched several videos on how to make soap the REALLY old-fashioned way, and after several hours of viewing, I decided to give it a shot.

I had collected about 1/3 a 5 gallon bucket of ashes from our fire pit. I screened them through a sieve to get the big chunks of ash out and then added both distilled and rain water. Then I let it sit for 10 days. The way to see if the solution is strong enough for soap is to put an egg in it, and if the egg floats, it's ready. I tried the egg test on the water in the bucket, and the egg sunk to the bottom of the water, so I knew I had to cook the mixture down to get the lye solution strong enough to make soap. Yesterday, I got a fire going to get some good, hot coals in the fire pit, and then I poured the water into my cast iron pot that I bought specifically for soap-making and put it on the fire to cook down.

|

| Lye water |

|

| Getting ready to cook down |

|

| Strengthening the solution |

I had vinegar ready in case any lye got on me accidentally, and I did feel a little burning on my wrist at one point. I wiped some on the spot with a rag, and it neutralized it right away.

The lye solution cooked for about 2 hours. I tried the egg test several times, but the egg kept sinking to the bottom of the pot. After the solution was down to about 1/4 of what I started with, I tried the egg again, and this time, it floated and I saw about a quarter-size piece of the egg sticking out of the top of the solution. I figured this was close enough.

|

The egg floating in the lye solution

|

I needed to strain the lye, so I used an old t-shirt. I should have used muslin or linen, but since I was putting it in a pyrex measuring cup, I cheated on this too.

|

| The leftover ashes strained out of the pot |

Once I had the ashes strained out of the lye solution, I lifted the fabric out of the measuring cup, being careful not to get any liquid on me. This is what I had left.

|

| Lye solution |

Now it was time to make the soap. The recipe I found on YouTube that seemed the most straightforward was 2 cups lard, 3/4 cup lye, and 1 tsp salt. The salt helps the soap set up better. I got the ingredients ready.

|

| 2 cups lard |

|

1 tsp salt into which I poured 3/4 cup lye solution

|

Next, I had to melt the lard. I washed out the lye residue from the kettle and put the lard in it then put it on the coals again. It took just a few minutes for the lard to melt until it was clear. Then I added the lye/salt solution to the melted lard.

|

| Lard melting on the fire |

|

| Lye/salt solution and melted lard |

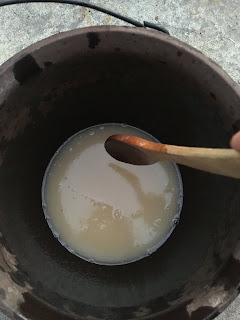

When you add lye to fat, it should immediately turn white-ish. The chemical reaction happened right away, and I began to stir.

|

| Soap has begun |

You have to stir continuously until you get "trace." Trace is when you pull your spoon through the mixture, and it leaves a line behind it. The mixture should thicken as well, almost like gravy or melted ice cream. I stirred...

...and stirred...

...until I got trace.

|

| Blurry, but you can see how the mixture is separating behind the spoon |

I had stirred close to an hour, and the mixture felt thick enough, and I had gotten trace, so I decided to pour it into the mold. Since I was making only a small batch, and I didn't have time to make a wooden soap mold, I used a silicone bread mold I got at the Goodwill. Yes, cheating again. I poured the mixture into the mold and now I wait. It has thickened into a pudding now, and I'm hopeful that it will actually set up enough to cut into bars.

.

|

| Setting up |

This really got me to thinking about the skills necessary to live in the past. The women who made the soap were chemists in their own right, creating chemical reactions without exact measuring, in order to make soap for their families. I think that my soap may not set up. I'll actually be surprised if it does, and if it fails, it's no big deal to me. I can go to the store and get more lard, and making lye, while time-consuming, isn't hard, and I have time. But back 200 years ago, if the soap didn't work, all of the lye and lard that was used was wasted. She had to be good. She had to be smart. She had to know what she was doing.

Hats off to all of the soap-making women of the past! Your skills put me to shame!